The UPC – an Irish perspective

| 1 June 2023 marked a significant step forward for patent protection and enforcement in Europe with the commencement of the Unified Patent system. It created a Unitary Patent, that provides uniform protection and equivalent effect across all participating Member States under the jurisdiction of one court, the Unified Patent Court. |

Introduction

The Unitary Patent system entered into force on 1 June 2023. It builds on the European Patent Convention (EPC) by forming a centralised path to grant, protect and enforce European patents. There are two pillars to the new system: Unitary Patents which are a new single patent that provide uniform protection across participating Member States, and the Unified Patent Court that provides a centralised forum for the litigation of those Unitary Patents.

Member States must ratify the UPC Agreement before they can participate in the new system. Ireland is a signatory, representing a non-binding intention to comply, but has yet to ratify so is yet to become a participating Member State.

The Unitary Patent

Previously the European Patent Office (EPO) accommodated central application and grant of patents, but legally a patent granted by the EPO remained a bundle of national patent rights. There has never been one “European patent”, as such, covering multiple EU countries, despite there having been efforts to create one since establishment of the EPO in 1973. The new application process, still administered by the EPO, will now grant a single “Unitary Patent” that has uniform transnational protection and equal effect in the participating Member States.

The Unified Patent Court

Disputes in relation to a Unitary Patent will be handled by the newly established Unified Patent Court (the UPC) (see diagram). It comprises a Court of First Instance, made up of individual Local Divisions and three Central Divisions. Each Central Division has specific jurisdiction over certain types of patents, according to the international patent classification. Two or more Member States can form a Regional Division – e.g. the Nordic Baltic Regional Division was formed by Sweden, Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania. A Court of Appeal will hear appeals, and the CJEU will hear requests for preliminary rulings on questions of EU law.

.jpg)

The impact of Member States joining at different times

There are 17 Member States currently participating in the Unified Patent system, having ratified the UPC Agreement. Ireland and six other Member States have signed, but have not yet ratified. Three Member States will not be participating (see diagram). The staggered timing of Member States joining will create some complexity, by resulting in different “generations” of Unitary Patents, as unitary protection is only provided for the territories of Member States in the system at the time of grant. A Unitary Patent granted today will have unitary effect in the current 17 participating Member States, but protection will not later be extended to territories of Member States that join at a later time. However unitary patents granted at that later time will benefit from protection in the extended territory. This will create interesting challenges for cases involving infringement of multiple patents of different generations.

“Opting-out” of the UPC

European patents already granted prior to 1 June 2023 (referred to as “classic” European patents) will automatically enter the UPC system, unless the patent is “opted-out” from the jurisdiction of the UPC – a classic patent can be opted-out at any time within the first seven years (known as the “Transitional Period”). Opt-out status remains for the life of the patent, it can be withdrawn once, but once withdrawn the patent cannot opt-out again.

There has been significant interest in the opt-out opportunity, with over 600,000 classic European patents having been opted-out so far. Many companies are opting-out their patents until the UPC has been tried and tested. This is to avoid, for example, exposing a valuable patent to the prospect of one invalidity hit, on a pan-European basis, by the UPC. That may be just too high a risk in the early days even if it means the need to take separate infringement actions in different Member States when it comes to enforcing the patent, and forgoing the possibility of one pan-European injunction against infringement.

The UPC in operation

(i) the Jurisdiction

An infringement action must be started in the Local Division or Regional Division where an alleged infringement is occurring or where the defendant is resident or has its place of business. On the basis that most large-scale patent litigation involves pan-European actual or threatened infringement, this will allow for forum shopping.

The exclusive jurisdiction rules of the UPC are relatively straightforward, subject to one exception, and can be summarised as follows. The UPC has exclusive jurisdiction over Unitary Patents and non-opted-out classic European patents. It has no jurisdiction over opted-out classic European patents. The one exception is that during the seven year Transitional Period, actions for infringement or revocation of non-opted-out classic European patents may be brought in the UPC or the national courts – the party bringing the action has a choice. Interestingly, once an action of this nature is initiated in the UPC the patent is “locked into” the UPC system, and national courts of the participating Member States must in future decline jurisdiction over it. Similarly if the action is initiated in a national court the patent is locked out of the UPC, and all further actions must be before the national courts.

(ii) the Procedure

As mentioned, infringement actions are brought before a Local Division or Regional Division. Invalidity / declarations of non-infringement actions are brought before the relevant Central Division. Where an invalidity action is brought by way of counterclaim in an infringement action, the Local Division has discretion to either hear it or it may “bifurcate” the matter by referring the invalidity aspect to the Central Division. Bifurcation in patent litigation is where claims of infringement and validity of a patent are decided independently of each other in separate court proceedings at different courts. It arises due to the different competencies of courts in civil law jurisdictions. Germany is probably the best-known example, where infringement proceedings can be brought before various regional courts, but invalidity is determined by the Federal Court in Munich. Common law systems (such as Ireland) typically do not bifurcate. It will be interesting to see how the bifurcation concept develops in the new system. On timing, the UPC has confirmed it expects to proceed to hearing within 12 months of an action being commenced.

(iii) the Law

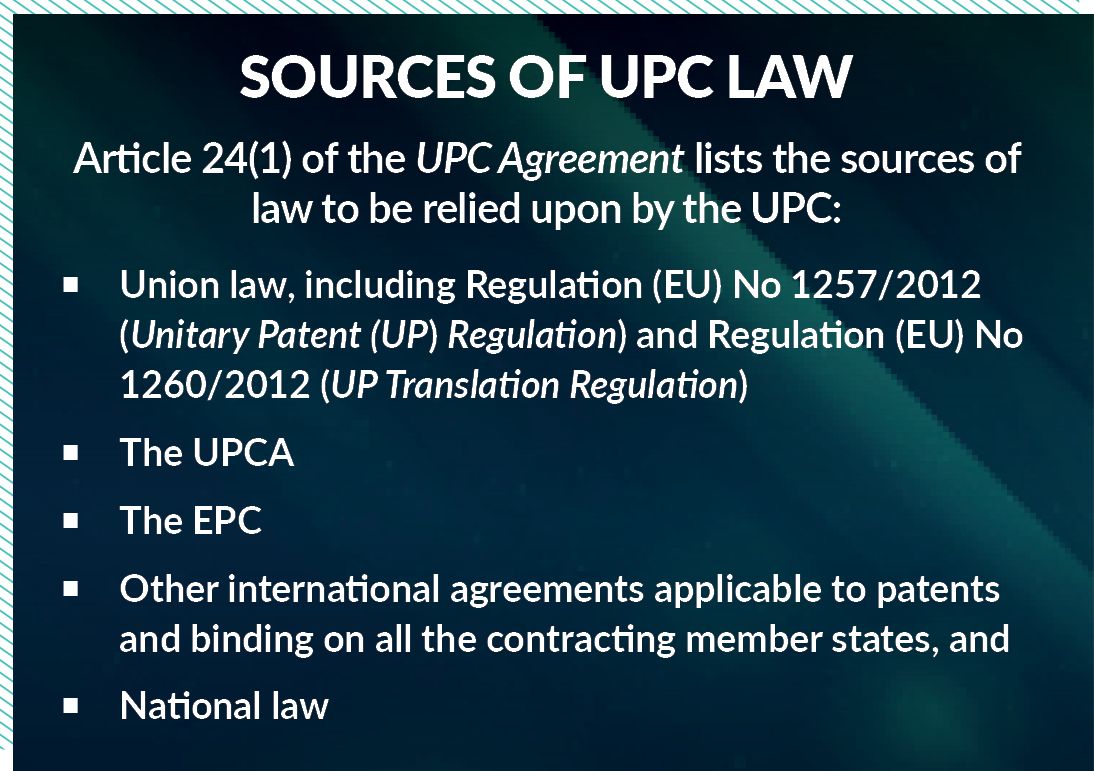

Article 20 of the UPC Agreement provides for the primacy of EU law. Article 24(1) lists the sources of law upon which the UPC must base its decisions (see diagram). The prevailing view is that this is a hierarchical list. National law features (albeit well down the list) which may mean that different panels of judges at the various divisions may have, and would be entitled to have, certain predispositions to their own national law. The UPC Agreement itself contains a set of procedural rules that represent both civil law and common law principles earning itself the description of a mixed civil/common law system.

(iv) the Judiciary

There are three legally qualified judges on each Local Division, with a minimum of one and a maximum of two judges from the host Member State. A technical judge with proven expertise in the relevant field of technology may be added as a fourth judge. Due to a weighting system connected to the number of patent cases in any jurisdiction prior to joining the UPC system, an Irish Local Division would likely comprise a panel of one Irish judge, and two chosen from the international pool by the President of the Court of First Instance. Two national judges appear to be the average number appointed in the majority of Local Divisions established so far. Judges are appointed for a term of six years, but are not precluded during their tenure from the exercise of other judicial functions at national level.

Impact on Patent litigation in Ireland

Ireland has its fair share of patent litigation and often features as one of the key jurisdictions in international patent litigation campaigns. A typical pan-European battle will involve the UK, Germany and France (being homes to the large markets), often the Netherlands (for its unique approach to extra-territorial patent jurisdiction), and Ireland often because core commercial operations are located here. Ireland’s industrial policy for the past 30 years focussing on foreign direct investment has meant a disproportionate amount of research, development and manufacturing operations take place in Ireland. As a result, if a multinational believes a competitor’s sales in Europe should be enjoined, where better place to go than the source of production.

The Irish courts have a strong international reputation in patent litigation and produce some of the best judgments internationally. We have a dedicated Intellectual Property and Technology List in the Commercial Court, high calibre of judges, and offer litigants the only English-speaking, common-law system available to them in the EU. We have much to offer when it comes to strategic pan-European litigation. That will remain the case while we sit outside the UPC system, but it is still in our interests to ratify the UPC Agreement. As things stand, and until we join, Unitary Patent owners still must apply separately for an Irish patent, and their Unitary Patents are not enforceable in an Irish court.

The UPC is at a crucial stage of development and Ireland should play its part in shaping it. Upon joining we will be the only participating Member State with practical experience of common law principles and procedures, many of which have been carried into the rules of the new system, but with which our civil law colleagues may not be as familiar – e.g. aspects such as the duty of full disclosure, common law interlocutory tests, Arrow declarations, cross examination of experts, experiments, security for costs, discovery etc. We shouldn’t underestimate the part we can play, nor the opportunity. When US multinationals are looking where to commence their UPC actions, they may find the only Local Division with a common law background and influence a very attractive proposition.

The UK will remain outside the system due to Brexit. The English courts will still remain busy with largescale patent cases, alongside the UPC. As a result there is a view that Europe will in time become bi-jurisdictional for pan-European patent litigation – with parties issuing parallel proceedings before the English courts and the UPC. That could put Irish practitioners in some unchartered territory when advising clients if parallel proceedings are also issued here. English judgments have persuasive authority in Ireland, but it is predicted that UPC jurisprudence, influenced by civil law judges, may in time begin to diverge from English law on particular areas of law and procedure. That said, the best way to address the concern is clearly to join the system, get involved and positively bring Ireland’s common law influence to bear on the new system.

Next Steps

Ireland signed the UPC Agreement in 2013, and heads of the Amendment of the Constitution (Unified Patent Court) Bill were approved by the Irish Government on 23 July 2014. We need to hold a referendum before we can ratify the UPC Agreement, as it entails a transfer of jurisdiction in patent litigation to the UPC, and an amendment to Article 29 of the Constitution will be required adding the UPC Agreement as an international agreement. Once ratified, Ireland intends to set up a Local Division of the UPC. Latest indication from the Irish Government is that a referendum on the UPC could be held in early June 2024 to coincide with local and European elections. We will have to wait and see.

For more information please contact John Whelan (Partner), Sarah Douglas and Sean Dwyer (Solicitors) or your usual Patent team contact.

Date published: 25 October 2023

This was published in the October edition of the Law Society Gazette 2023

|

LOOK IT UP LEGISLATION: Rules relating to Unitary Patent Protection (OJ EPO 2022, A41) Agreement on a Unified Patent Court (2013/C 175/01) Rules of Procedure of the Unified Patent Court WEBSITES: |